Honoring Henrietta Lacks: When Art, Research, and Justice Combine

February 6, 2021

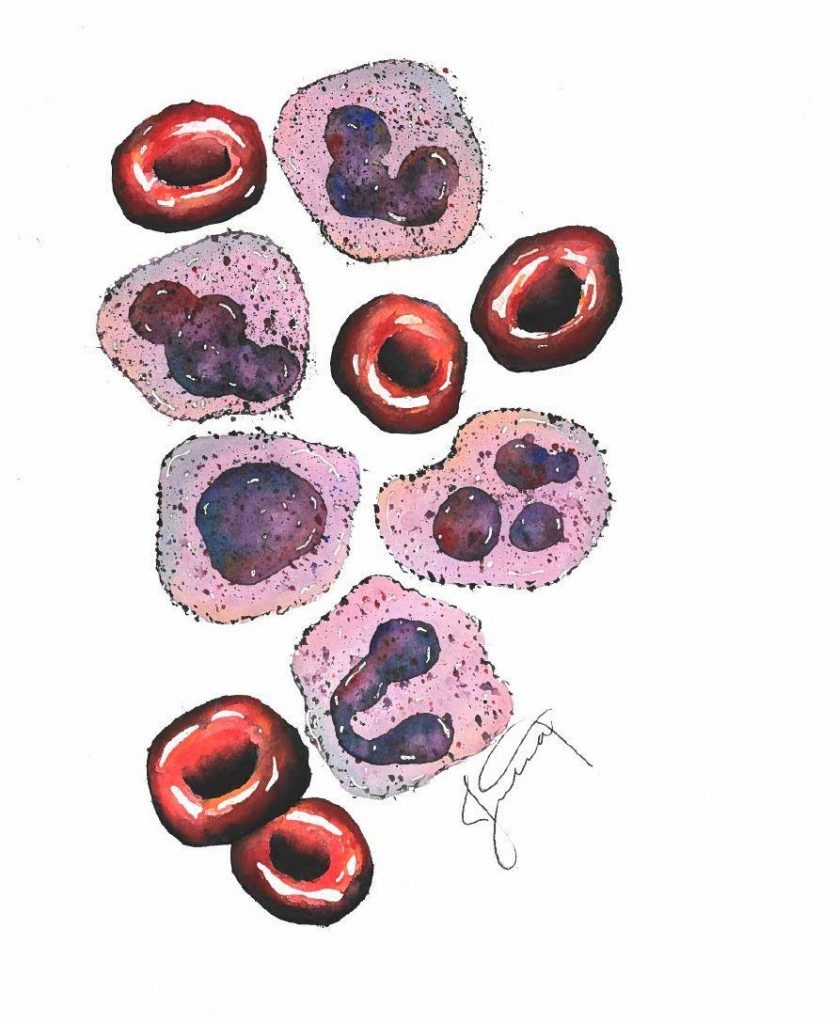

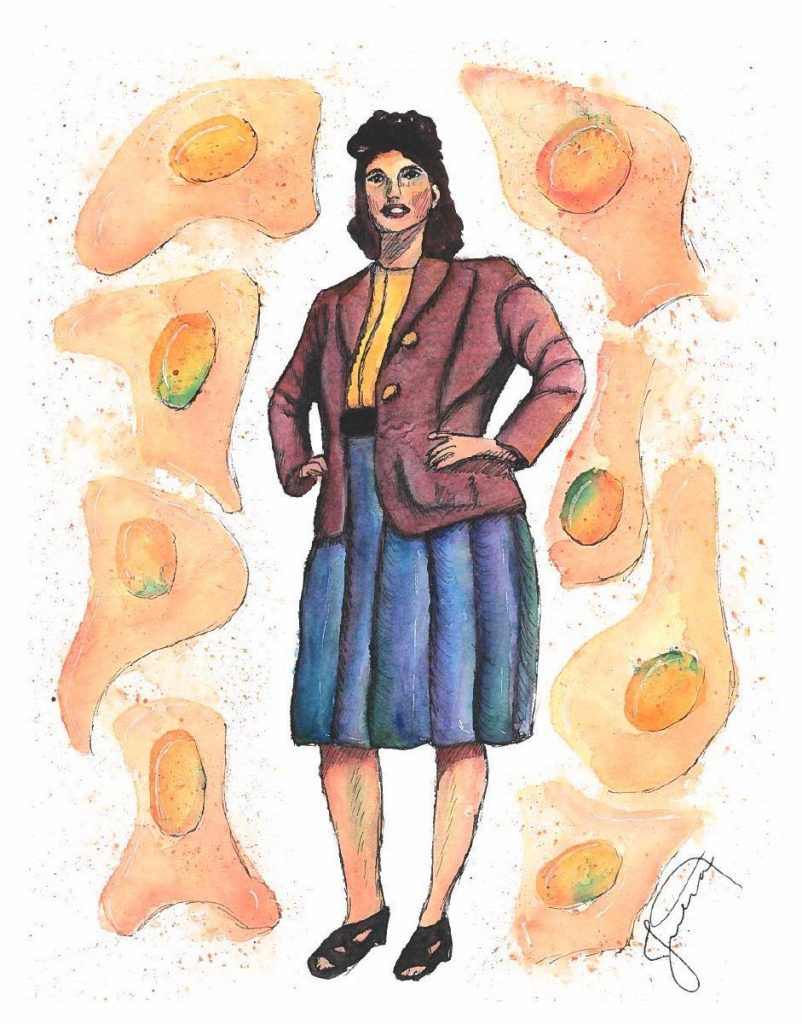

By Dr. Erin A. Henslee, Assistant Professor, Department of Engineering

HeLa cells were the first discovered immortalized human cell line (cells that can be continuously grown) in 1951 and have since become one of the most important cell lines in medical research. What many people using this cancer cell line did not know, was that these cells were unknowingly harvested from a 31-year-old African-American woman being treated for cervical cancer at Johns Hopkins Hospital. This woman’s name was Henrietta Lacks. She was a wife, a mother of five children, and had battled her aggressive cervical cancer for nearly a year before her death. She was buried in an unmarked grave in Virginia.

HeLa cells were used in the 1950’s to develop the polio vaccine, were the first cells ever cloned, have helped researchers study cancer treatments and viruses, and have been used in more than 11,000 patents and 60,000 publications. The connection between HeLa cells and Henrietta Lacks did not surface until the 1970’s when HeLa cells began to invade and contaminate other cell samples. The family only found out because researchers began to contact them, asking them for DNA so that they could figure out how to separate HeLa DNA from their other samples.

In 2013 researchers began publishing the DNA sequence of the genome from HeLa cells. Her family fought to have the publications pulled due to privacy (this was their genetic information). Under a new agreement with the National Institute of Health (NIH), Lack’s genome data is now only accessible to those who apply for and are granted permission. Additionally, two representatives of the Lacks family now serve on the NIH group that reviews these applications. Further, any researcher who uses that data is asked to include an acknowledgement to the Lacks family in their publications.

Lacks’ story was made famous in 2010 upon the publication of Rebecca Skloot’s book, “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks,” and became a movie, starring Oprah Winfrey, in 2017. The story portrayed in The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks points to several important ethical issues, including informed consent, privacy, compensation, and communication with donors and research participants.

As a researcher who regularly uses HeLa cells, and who was sadly ignorant to their significance until just a couple of years ago, I ask that we all use this story to reflect on our own practices. We must not lose sight of the humanity in our work and we must hold ourselves accountable to right injustices. For my part, I will ensure my research students are aware of Henrietta Lacks, how the medical profession failed her and her family for so long, and how we must be better. As I now have the responsibility of corresponding author, I will include acknowledgements to those we owe the research. As we celebrate Black History Month, I ask that we all honor the legacy of Henrietta Lacks. A headstone, donated to Henrietta’s family by an early HeLa researcher, Dr. Roland Pattillo, perhaps provides the best final words:

“In loving memory of a phenomenal woman, wife and mother who touched the lives of many Here lies Henrietta Lacks (HeLa). Her immortal cells will continue to help mankind forever. Eternal Love and Admiration, From Your Family.”

For more on Henrietta Lacks, please consider reading:

Skloot, Rebecca. The immortal life of Henrietta Lacks. Broadway Paperbacks, 2017.

Wake Forest’s Liberal Arts Engineers:

Artist, Julia Powers

As Fall 2020 wrapped, I stared at the new, blank, walls of our (Dr. Kyana Young’s and mine) brand new lab at Wake Downtown and began searching Etsy for wall hangings I could buy to make the lab feel more like home. I shared some of the ideas with my research group over Zoom. With everyone dispersed at Thanksgiving, there was not much “lab” stuff to discuss besides looking forward to continuing work in 2021. It was then my research student, Julia Powers (EGR ’23), revealed she was pursuing an Art minor and offered to paint some designs herself over the break. I spent the weeks over break eagerly anticipating the results. When Julia delivered her two paintings and I finally had them in my hands, I was blown away! I am so excited to share her talent with you all and want to extend a huge THANK YOU to Julia for sharing her talents with me. It also led me to reflect on how happy I am to be a part of Wake Forest Engineering. It has been such a privilege to be around our Wake Forest Engineering students who bring so many talents to our Department. I have gotten to hear you sing and play instruments, watch you compete in NCAA sports, eat food you have prepared, witness your participation in service and clubs, and continuously benefit from your perspectives in class and random hallway conversations. Thank you for sharing your talents with us!